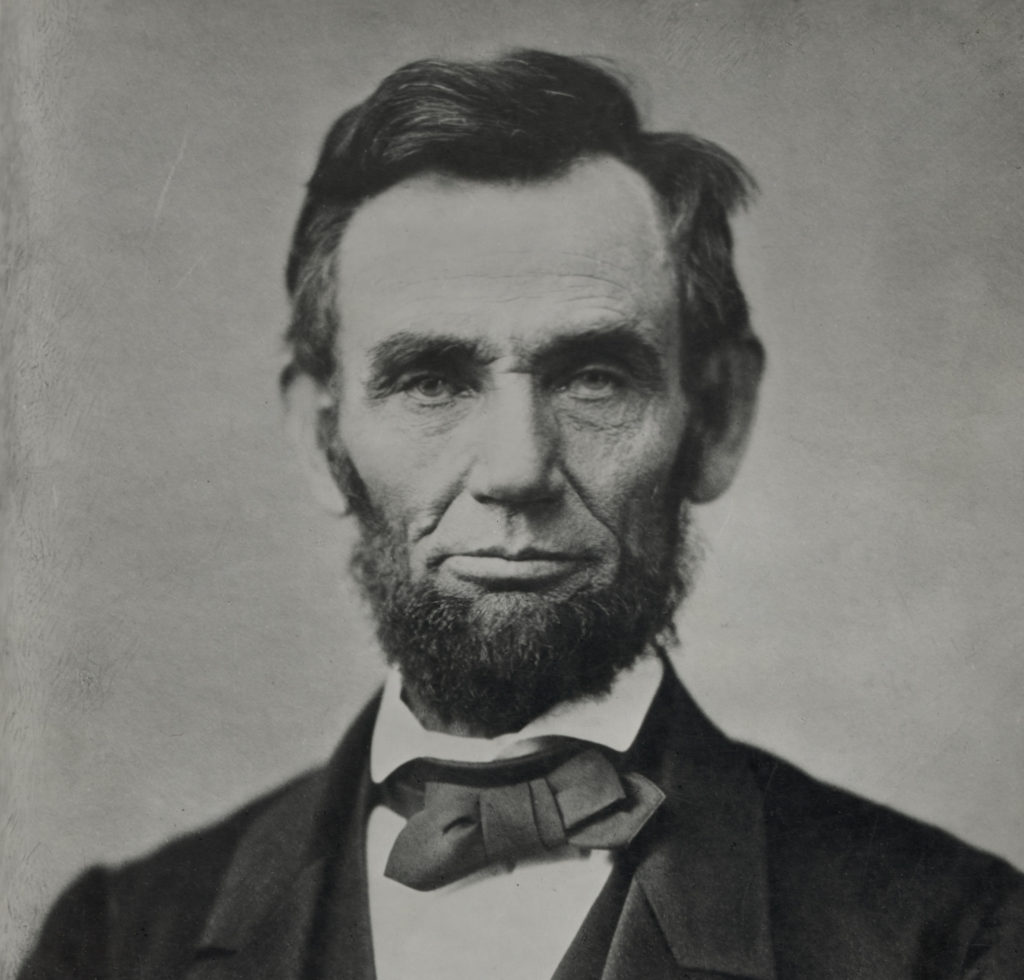

More books have been written about Abraham Lincoln than any historical figure save Jesus Christ. So, there is not much I can add to what has already been said about our 16th President. What I want to do instead is apply one aspect of his wisdom to modern-day leadership.

David Reynolds’ 2020 book, Abe: Abraham Lincoln In His Times, is a biography of Lincoln that details the various cultural forces present in his day. The most obvious being the battle between abolitionists in the North and slave holders in the South. By the time Lincoln became a relevant national figure in 1858, this debate was at a fever pitch and the country was on the brink of war.

One aspect of the book that makes it worthwhile for leaders is its demonstration of how Lincoln used language to pursue his belief that slavery needed to be abolished. Unlike some of the more arduous abolitionists of his day, Lincoln often clothed his rhetoric in moderation. He did this for two reasons. First, he wanted to ensure that he could attract the most people to his side. Leaders, as I write often here, are those others follow. So, what good would it do Lincoln to use language that could possibly alienate those on the fence? Admittedly, those of us in the twenty-first century have a hard time understanding how anyone could be on the “fence” with slavery, but history details how many there really were.

Next, Lincoln also used language of moderation to advance his own agenda. We don’t think of Lincoln as a politician, but in reality he was. Lincoln was “political” in the sense that he understood how his words would either attract, or detract, others. So, in the political sense he had to ensure that he could attract enough votes to gain the positional authority—the Presidency—to achieve his aims. While historians still debate whether the Lincoln of 1860 believed in the full emancipation of slaves, or whether it took three years of civil war for him to get to that point, what is apparent is that Lincoln was intentional in the years leading up to his Presidency with regards to the slavery issue.

The point for modern leaders to consider is that of language. Does the language unite, or divide? If it is the latter, not only are followers lost, but influence is also lost. To that end, we need to consider what is worth losing influence over and what is not. For example, is it worth losing influence over the political issues of our modern day? Or, is there a deeper cause worth fighting for that people can unite to? Only the leader can answer that question.

What is apparent in our day is the power of language. Admittedly, I am free speech advocate. This means I welcome debate, especially the kind that I do not agree with. To that end, I am troubled by the silencing that is going on in our country even though, often times I do not agree with the views of those being silenced.

My encouragement to those people, however, would be to use language in a more effective matter much like Lincoln did. Please note, history states that many still disagreed with Lincoln. After all, the bloodiest war in our country’s history was fought after he was elected President, but, he made every attempt to unite the nation with conciliatory language, as evidenced in his second inaugural:

“With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.”

Despite Lincoln’s best efforts, however, he was gunned down 41 days later by someone present when he said the above, John Wilkes Booth.

I close here because despite our best efforts, our language may still divide. As leaders, however, we are responsible for making effort to unite and bring people together. Our nation has progressed because this is what Abraham Lincoln did.